Nonparametric estimation

If time allows, this will be covered on Feb 4. Here are slides

Under the assumption of conditional exchangeability given a sufficient adjustment set \(\vec{X}\), the average causal effect within subgroups defined by \(\vec{X}\) is identified by the difference in means across the treatment \(A\) within this subgroup.

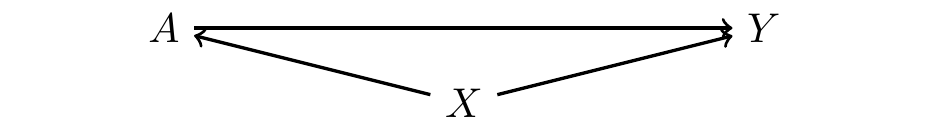

This page walks through how to estimate that difference in means and (optinally) re-aggregate the conditional average causal effects to average causal effect estimates. We illustrate in a simple case represented by the DAG below.

In our illustration, the treatment a is binary and the outcome y is numeric. The confounder x is a sufficient adjustment set and takes the value 0, 1, or 2.

You can simulate a dataset of 1,000 observations by running the code below.

library(tidyverse)

simulated <- tibble(id = 1:1000) |>

mutate(

x = rbinom(n(), 2, .5),

pi = case_when(

x == 0 ~ .3,

x == 1 ~ .5,

x == 2 ~ .8

),

a = rbinom(n(), 1, pi),

y = rnorm(n(), mean = x*a),

# For illustration, we include a sampling weight variable

# because in real settings there may be sampling weights

sampling_weight = 1

)Estimate CATEs by subgroup means

To estimate the conditional average effect, we first group the data by the confounder x and treatment a. By conditional exchangeability, the rows with a == TRUE and the rows with a == FALSE are each a simple random sample of all rows within the subgroup defined by x, so we can estimate the mean outcome \(\E(Y^a\mid X = x)\) by the subgroup sample mean, \(\E(Y\mid A = a, X = x)\).

\[ \hat{\text{E}}\left(Y^a\mid X = x\right) = \underbrace{\frac{\sum_{i:X_i=x,A_i=a}Y_i}{n_{x,a}}}_{\substack{\text{Sample mean}\\\text{in subgroup}\\X = x, A = a}} \]

average_potential_outcomes <- simulated |>

# Group by confounders and treatment

group_by(x,a) |>

# Summarize weighted mean of Y, weighted by sampling weights

summarize(

mean_y = weighted.mean(y, w = sampling_weight),

.groups = "drop"

) |>

print()# A tibble: 6 × 3

x a mean_y

<int> <int> <dbl>

1 0 0 -0.0384

2 0 1 0.188

3 1 0 0.0994

4 1 1 0.953

5 2 0 -0.0851

6 2 1 1.95 As expected, the code above produces estimates for the mean of y within subgroups defined by x and a. The conditional average causal effect is difference in y across values of a, within subgroups defined by x. To take this difference, we pivot wider.

cate <- average_potential_outcomes |>

# Pivot wider and difference over A to estimate CATE

pivot_wider(

names_from = a,

names_prefix = "mean_y",

values_from = "mean_y"

) |>

mutate(cate = mean_y1 - mean_y0) |>

print()# A tibble: 3 × 4

x mean_y0 mean_y1 cate

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0 -0.0384 0.188 0.226

2 1 0.0994 0.953 0.854

3 2 -0.0851 1.95 2.03 As expected, the code above estimates the Conditional Average Treatment Effect (CATE) within each population subgroup defined by the pre-treatment variable x.

Re-aggregating to ATE

To determine the overall average treatment effect, we can re-aggregated the CATE estimates weighted by the size of each stratum: how many people have x == 1, x == 2, and x == 3. First, determine the size of each stratum.

\[ \hat{\text{P}}\left(X = x\right) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_i \mathbb{I}(X_i = x) \]

stratum_sizes <- simulated |>

# Count sum of sampling weight in each stratum

count(x, wt = sampling_weight) |>

# Convert count to a proportion of the population

mutate(stratum_size = n / sum(n)) |>

print()# A tibble: 3 × 3

x n stratum_size

<int> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0 244 0.244

2 1 479 0.479

3 2 277 0.277Then merge and take the weighted mean of CATE over the strata.

\[ \hat{\text{E}}\left(Y^1-Y^0\right) = \sum_x \hat{\text{P}}(X = x)\left[\hat{\text{E}}\left(Y^1\mid X = x\right) - \hat{\text{E}}\left(Y^0\mid X = x\right)\right] \]

ate <- cate |>

left_join(stratum_sizes, by = join_by(x)) |>

summarize(ate = weighted.mean(cate, w = stratum_size)) |>

print()# A tibble: 1 × 1

ate

<dbl>

1 1.03Estimate by treatment weights

One can equivalently take a sampling view of causal inference. When I observe a unit \(i\) with outcome \(Y_i = Y_i^{A_i}\), the probability of observing this outcome is the product of the probability that the unit was sampled multiplied by the probability that the unit received treatment value \(A_i\), conditional on confounders. Just as one generates sampling weights for descriptive population inference by the inverse of the probability of sample inclusion, one can generate inverse probability of treatment weights for causal inference. The full weight for each unit \(i\) is then the product of these two weights:

\[ w_i = \text{SamplingWeight}_i\times \frac{1}{\text{P}(A_i\mid X_i)} \]

The code below constructs these weights.

data_weighted <- simulated |>

# Within confounder subgroups, determine the probability

# of the observed treatment

group_by(x) |>

mutate(probability_of_a = case_when(

# For treated units, proportion treated

a == 1 ~ mean(a),

# For untreated units, proportion untreated

a == 0 ~ mean(1 - a)

)) |>

# Calculate the total weight as the product

# of the sampling weight and the inverse probability of treatment

mutate(

total_weight = sampling_weight * (1 / probability_of_a)

) |>

ungroup() |>

print()# A tibble: 1,000 × 8

id x pi a y sampling_weight probability_of_a total_weight

<int> <int> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 1 0.5 0 0.969 1 0.547 1.83

2 2 2 0.8 1 3.48 1 0.819 1.22

3 3 1 0.5 1 1.71 1 0.453 2.21

4 4 0 0.3 0 -0.797 1 0.709 1.41

5 5 0 0.3 0 -0.603 1 0.709 1.41

6 6 1 0.5 0 -1.98 1 0.547 1.83

7 7 1 0.5 0 0.216 1 0.547 1.83

8 8 2 0.8 1 1.65 1 0.819 1.22

9 9 0 0.3 0 -0.416 1 0.709 1.41

10 10 2 0.8 1 1.51 1 0.819 1.22

# ℹ 990 more rowsOnce we have weights, we can directly estimate the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) by the mean difference in the weighted average outcomes in each treatment group,

\[ \hat{\text{E}}(Y^a) = \frac{\sum_{i:A_i=a} w_i Y_i}{\sum_{i:A_i=a}w_i} \] and report the difference in the estimated \(\hat{E}(Y^1)\) and \(\hat{E}(Y^0)\).

data_weighted |>

# Summarize weighted mean outcomes within treatment groups

group_by(a) |>

summarize(

estimate = weighted.mean(

y,

w = total_weight

)

) |>

# Difference across treatment groups and estimate the ATE

pivot_wider(names_from = a, names_prefix = "mean_y", values_from = estimate) |>

mutate(ate = mean_y1 - mean_y0) |>

print()# A tibble: 1 × 3

mean_y0 mean_y1 ate

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0.0147 1.04 1.03Comparing the two estimates

Above, we illustrated two strategies to estimate the Average Treatment Effect.

- Estimate the CATE by subgroup means of \(Y\) within \(X\) and \(A\), then aggregate across strata weighted by size.

- Estimate the probability of treatment \(A\) given \(X\), then estimate the ATE by a weighted mean.

You may notice that the estimates by the two approaches are mathematically identical. At least under nonparametric estimation, one can show that these two estimators are two different ways of thinking about the exact same estimation process.

Concluding thoughts

Nonparametric estimation is worth knowing because of its simplicity: estimate the conditional average causal effect within subgroups by taking the difference in mean outcomes within subgroups. However, nonparametric estimation only works in practice when the confounding variables take only a few discrete values (in this example, x was always 0, 1, or 2). In realistic settings, there are often many confounding variables that take many values each. For this reason, causal effects are most often estimated in practice by the model-based methods that we will learn next.